Can Change Managers Change Well? Retirement and Managing One’s Own Change

Based on a variety of personal reasons (none of which include physical ailments or having won the lottery), I recently laid down my tools and stopped working. I am both sad to leave my chosen career in change management, and happy to go. Saying goodbye to something is always going to hurt, even if it’s something you want to say goodbye to. That’s the kicker with change, it ALWAYS needs to be managed.

Even though I am completely onboard (having confirmed this through copious stakeholder engagement with myself) co-designed it, and know its benefits, it has still required thoughtful planning, good communication, and a lot of support. Sound familiar?

As change management practitioners, we know the theory well. But specialists often don’t take their own advice, and we are no exception. As professional change managers we are often in danger of leaving ourselves out of the change process, expecting that because we know the theory it will all be unnecessary for us. We have helped manage hundreds of changes, taught and written about it. We believe we will simply fly through it, barely tracking our progress on one of our many visual aids or AI data gathering tools.

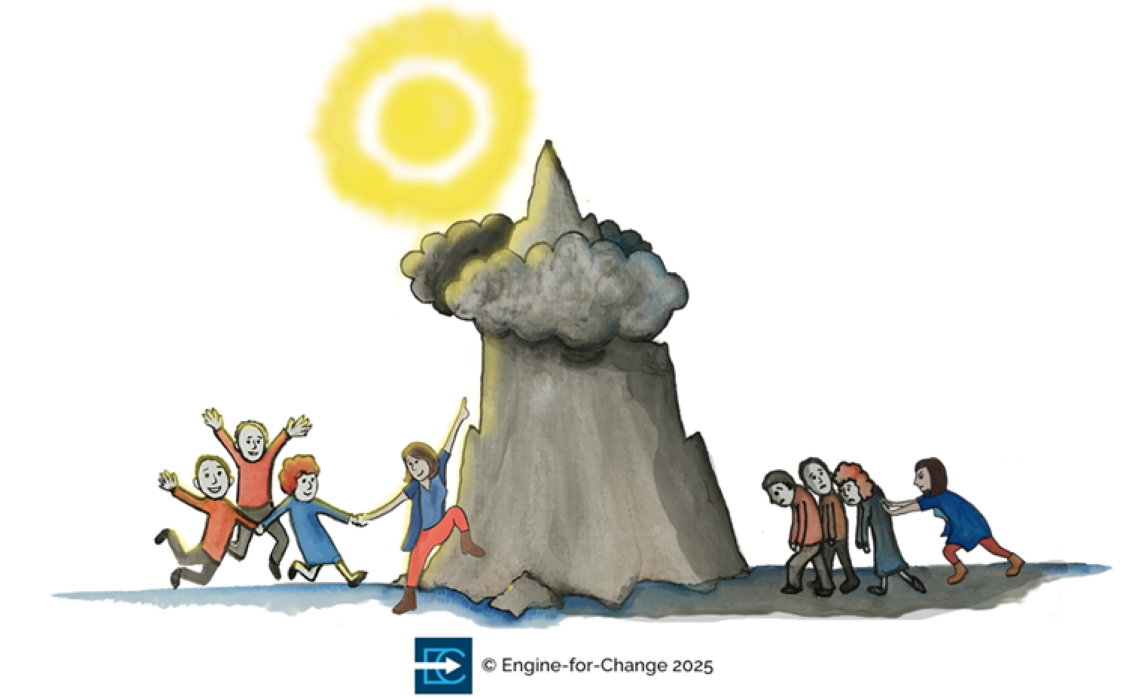

Not so colleagues! I have been humbled as I experience this change from ‘the inside’. And it’s not the content of the change. I am happy to have retired and still sure of my decision. It’s the change itself, the transition, that is fundamentally hard, physically, mentally and emotionally.

So, what has helped? The same things that have always worked!

- Do some planning

- Communicate the plan

- Provide support for the people navigating the transition

1. Do some planning

The more you have thought about why a change is happening and what you want it to look like the better prepared you can be. My transition to retirement has been a bit of a rocky road and an emotional rollercoaster. I needed to get clear on my motivations and the driving forces, as this knowledge would be necessary for addressing the challenges this change presented.

You will recognize the commonly used change planning questions of Why, When, How, What, and Benefits, I used to kickstart my planning.

a. When do I want to retire?

I started thinking about this question very early on, and it was a guestimate. My guess was initially ‘in five years’ but became seven as I was happy to continue in my role when that initial five years was up.

b. How much do I want to live on?

The money question is a central part of retirement-type change, so it needed careful consideration. I reframed the common question ‘how much do I need?’ to ‘how much do I want to live on?’ because it gave me more agency – which was an important part of having control in this change. It was also closely tied to how I might answer the When question. I did research and spoke to financial experts to get good advice to inform my decision-making. (Surprisingly, professional estimates of the how much question, were much more than our household’s experience of what we could live on.)

c. What am I going to do (instead)?

Every single person I told about my change to retire, asked me this question and I found it best to have a simple prepared answer for communication purposes.

I also needed an answer for myself – how would the future look different with this change? What might be possible with the extra time and energy I had?

This was the best part of the planning. A friend told me that in her last six months of work she kept a notebook by her desk, every time she thought of something she wanted to spend her time on in retirement she jotted it down.

My planned intentions include ballet, Italian language, and creative writing, all of which I love, and have always spent time doing but never to my heart’s content. Other intentions include doing one thing at a time, being present, eating lunch, being with family, friends, neighbors and community, napping, and exploring my local region and city.

2. Communicate the plan

The above planning helped me get clear in my head about my change. I used that clarity to identify what (and what not) to communicate with others. Communicating parts of this plan with friends, family and colleagues made it a reality and provided well needed support. Most people were more excited for me than I was for myself. They were really helpful as the retirement date came closer when I was anxious and sad.

Useful questions for my communication strategy were:

a. When do I want to begin communicating this?

I started five months in advance because I wanted to give fair warning to colleagues and clients who might be impacted by my absence.

b. Who do I want to tell?

I started with the people who were going to be on board with this and would have positive, supportive reactions. The last thing I needed was to be justifying my decision when I was going through the emotions of self-doubt, regret, fear. Resisters, fear-mongers, green-eyed monsters, and nay-sayers will be present but having done some planning I was better equipped to counter or avoid them, and not let them inside my head. I also consulted and communicated with those who had gone before me, soaking up their knowledge and experience to make my plan more realistic.

c. How do I want to announce this big change?

I told people that would be impacted by this, face to face and personally. I knew we would be in this together for a while and I would need their help.

I posted on social media with photos reflecting on my career, thanking people, informing a wide audience. I received well wishes, and thanks back which helped manage the emotions of leaving, be confident of my legacy, and made it real!

3. Provide support for the person navigating this transition

It is easy to fall into substituting a life of work by slotting in another activity, creating the same routine, with the same ‘other’ or ‘external’ focus. And I realized this would be a particularly profound change for me: to wean myself off the adrenalin addiction of constantly producing something for someone and being validated in that role, to being something different.

I am not 100% sure of what that is as I am currently in the ‘unknown’. That uncomfortable state of having left the old but not yet created the new. It is hard, and requires a lot of self- care and support, all of which is highly personal and can take many forms. This is what has helped so far.

a. Boundary events (Bridges Transition Model)

I used rituals and celebrations to mark the transition from one state of being to the next. For me these were a retirement party with colleagues, retirement gatherings with friends, sitting in my garden on my first official day of retirement and reflecting on the benefits of retirement, changing the home page on my computer, filling my Favorites bar in my browser with non-work-related links.

b. Putting into practice things that help when I am grieving

I have been taking one day at a time, doing what I feel like rather than planning things in advance. Activities like coffees/drinks with friends, being in nature, writing in my journal, meditation, exercise, watching movies, baking. I am giving myself a ‘time-out’ to transition from a lifetime of structured, achievement-oriented living to one based on my individual, creative needs and desires.

c. Planning new, fun activities I would now have time/energy to do

I listened to the advice from my friend who retired six months before me and jotted down fun things I wanted to do after I retired. One example was ‘have a leisurely breakfast in the café across the road, then go for a stroll’. Other activities included inviting my young nephews to stay for some of their summer holidays, and planning long trips to places I had always wanted to go.

As seasoned change management practitioners we are fortunate to already have the tools, theory and knowledge when it comes to managing our own changes. But we need to apply them as seriously to ourselves as we would to any of our clients, to have faith in the processes that we know work, and to take advantage of our own skills and experience for our own greatest changes!