Walking an Unusual Career Path through Change

I got into change management by chance, when it was an unusual career path in Colombia. Back then, I would get odd looks when I told people what I did. I still do, sometimes, which makes me wonder if it still is an unusual career. I’d like to share my story because I have the feeling that many of us still struggle with putting in simple words what we do, and perhaps this will comfort some of those who are going through a professional identity crisis, like I once did.

The Beginning

My story starts with graduating university with a degree in political science and wanting to work in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). I applied for a CSR role at an interior design firm, which I did not get. Instead, they offered a role labeled as Learning & Development (L&D). When accepting the role, I didn’t really know what my employer was expecting from me, but they assured me that with my social science background and some upskilling I would be okay.

I came to understand that what they needed was someone that would support their clients and staff through adapting to newly renovated office spaces. These office spaces were colorful, open, and modern (very different from the 80’s cubicle look) but people seemed to have difficulty in adapting or even enjoying their new office space. People longed for their old cubicles, even though the new offices had naturally lit open working spaces, inviting kitchen areas, and even breakout rooms with Play Stations and Nintendo Wii. What they needed was change management! However, nobody was calling it that – and I had no idea that such a profession existed!

I was learning a lot about modern office design and figuring out what my role was because it seemed something different than learning and development. Even my interior designer and architect colleagues didn’t understand what my role was – and joked about me being a “management informant”. My family and close friends were pleased with me getting a job and naturally had a lot of questions – and I struggled to explain what I really did. Twelve years later, I still get asked a lot of questions about what I do – especially now that I work for a Cemetery Trust. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

A Realization

I still remember those first weeks at my new job. I remember doing what I know best and enjoy the most: researching. I did a lot of research around office design and human behavior. I learnt that for the most part of the 20th century the modular cubicle was the go-to design for office spaces. Modular cubicles meant personalization, privacy, and efficiency. Across the world, employees personalized their cubicles, and although they didn’t have doors as such, the enclosed space gave the impression of being off-limits. Fast forward to the early 2000s, and the new trend was (and continues to be) the open office floor plan. These open workspaces have very few dividing walls, and team members are accommodated in a single large, open room. Soon enough people started complaining about lack of privacy and overflow of distractions. The funky design and bright colors didn’t make up for the (perceived) loss.

And then, it clicked. People needed some guidance on how to navigate the new environment, and perhaps some time to adapt to it, too. Contrary to what employers expected, a newly renovated space wouldn’t immediately mean staff would be content, especially if they hadn’t been involved in the journey of change. For example, people couldn’t take private calls from their desks anymore, but there were quiet or private rooms that they could use instead. Suddenly, people had access to a Play Station at work, did it mean that they could start playing video games at 10am on a Wednesday? Also, people needed to adjust to endless interruptions: a colleague sneezing, or approaching to ask something, or side conversations happening just a few meters away.

Three Useful Concepts

As I was navigating this ill-defined role, I kept coming back to three concepts I had learnt at university that seemed useful to apply to the situation. They are sense-making (the process in which collective awareness and understanding is created); sense-breaking (the process in which collective understanding is broken, and no longer useful to explain the world around us); and sense-giving (the process in which sense-making is influenced to create a preferred shared understanding).

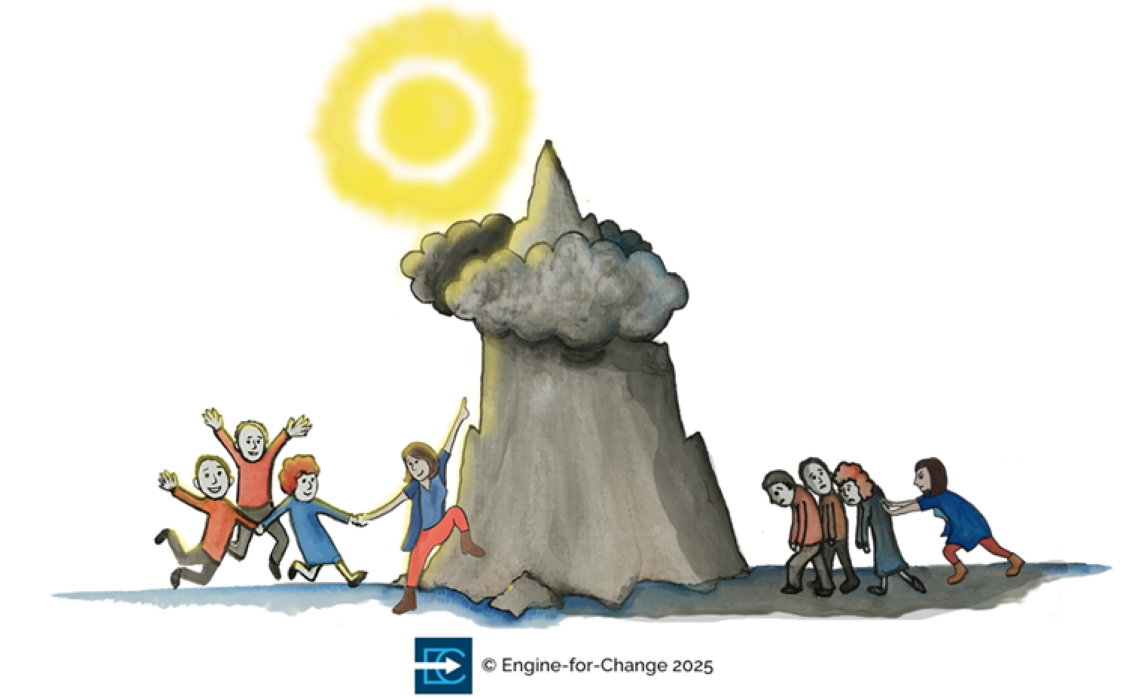

In essence, the group of people impacted by the office renovation (my stakeholders) were going through a process of sense-breaking (their understanding of an office environment was no longer valid to explain their new circumstances), and, at the same time, they were trying to make sense of their new reality. The sense they were making wasn’t very encouraging, though: they missed the old office, and the employer wasn’t appreciative of the resistance they were getting.

How could I, then, support them in making (better) sense of it? Was my role to sense-give by influencing a preferred shared understanding?

If I understood what their losses were and understood what the new offices had to offer by working closely with the architects, perhaps I could share that knowledge with them. Even more, if I understood the way in which employees were expected to use the spaces, perhaps I could share that too. Soon enough, I was completing change impact assessments, communications plans, training plans, and developing training content, but I didn’t call them that. I surely wasn’t following any change process or change framework. And I surely wasn’t doing any of that on convoluted Excel spreadsheets. That would come later.

The Need for Formal Training

I worked there from 2012 to 2014, two years that profoundly shaped the trajectory of my professional career. I had learnt so much on-the-job, but I felt that I might have been missing things because I didn’t have formal training. So I moved to Amsterdam to study a Masters in Culture, Organisation, and Management. This Masters in particular had an emphasis on sociology that others didn’t have. This was the place where I learnt more about change methodologies and frameworks, change impact assessments, change strategies, and more. It was also the place where I gained a better understanding of human and social behavior, such as cognitive biases and how these affect how we navigate the world around us, and how those impact our perceptions around personal and organizational change.

Defining my Work and Practice

My experience working as an unofficial Change Manager (my L&D job title never changed) at an interior design firm gave me some alternative adjectives to describe my role: I wasn’t a management informant as my colleagues once thought, or L&D as my job title said. At different points in time, I was a therapist, facilitator, trainer, copywriter, psychologist, coordinator. Some people even referred to me as “Arqui”, short for Architect in Spanish, since I worked for an interior design firm. I would experience a professional identity crisis for many years.

Even though I couldn’t define my role in the right words at that time, it did help me understand from a practical standpoint the essence of a Change Manager: to facilitate sense-making as people navigate through organizational changes, whether that is a move to a newly renovated workspace, the implementation of new technology, or a merger. Change Managers may rely on completing templates, plans, and strategies, but that’s not the end-goal.

I also got valuable lessons about how an organization’s built environment says as much about the organizational culture and organizational behaviours as the organizations’ values, and mission statements. I now pay attention to details such as how people make sense of their environment, and how they interact with it. This has been incredibly useful to consider as my current change management work is with a Cemetery Trust. (And that’s a story for another day.)

With the practical experience I had gained, my formal studies, my own research, and the slow traction that the change profession was getting within organizations in Colombia, I came to appreciate that I was professionally working in change management. However, I could still count with one hand how many fellow change practitioners I knew. It was only when I moved to Australia in 2020, that my professional network started to grow. I was more able to look for and find roles where the title and what I did had a closer fit. It has not been a straight path, but it has been my path.